The growth of artificial intelligence has brought attention to its impact on the environment. A study shows that AI produces much less carbon than humans when writing and illustrating.

But this doesn’t mean AI should replace human creators, the study notes.

Andrew Torrance, a law professor at KU, helped conduct this study. It looked at the carbon emissions of popular AI tools like ChatGPT and DALL-E2 compared to humans doing the same creative tasks.

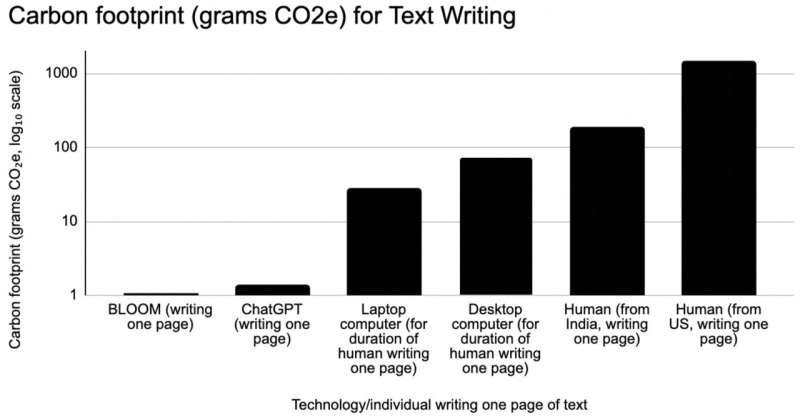

Just as with cryptocurrency, there’s a lot of debate around the energy consumption of AI and its environmental footprint. While we’ve long understood human-related emissions, we haven’t had many direct comparisons with AI’s impact. A recent study sheds light on this, showing that AI emits far less CO2e – 130 to 1,500 times less per page of written text and 310 to 2,900 times less per illustrated image than human processes.

Andrew Torrance, a co-author of the study, emphasizes the importance of data-driven conclusions over assumptions. “We’ve heard claims about AI’s efficiency in terms of emissions, but we needed solid data to confirm these claims,” he explains. The findings were clear: AI is significantly more eco-friendly in these areas, with even the most cautious estimates showing a vast difference. “The results were surprising, highlighting just how much less CO2e AI generates compared to human activities in these fields,” says Torrance.

The research, a collaborative effort involving Bill Tomlinson, Rebecca Black, and Donald Patterson from the University of California-Irvine, alongside Andrew Torrance, was featured in the journal Scientific Reports.

To assess the carbon footprint associated with a person engaged in writing, the team turned to the Energy Budget. This metric evaluates the energy consumption linked to specific tasks over a designated timeframe, providing a basis for their comparative analysis of human versus AI energy use in writing.

Researchers calculated the energy used by a computer running word processing software per hour and multiplied it by the time it typically takes to write a page (about 250 words). This way, they estimated the carbon footprint for human writing. They compared this to the energy used by AI systems like ChatGPT, which can write much faster, to find out AI’s carbon footprint.

They also looked at carbon emissions per person in the US and India. The US’s average is 15 metric tons of CO2e per year, while India’s is 1.9 metric tons. These countries were chosen because they represent the highest and lowest emissions among nations with over 300 million people. This comparison helps show the difference in human emissions worldwide against AI’s emissions.

The study found that Bloom AI has a much smaller carbon footprint when writing a page of text compared to humans. It’s 1,400 times less impactful than a writer in the U.S. and 180 times less so than one in India.

In the realm of digital illustration, DALL-E2 produces significantly less carbon dioxide. It’s about 2,500 times less than a U.S. artist and 310 times less than an artist from India. Midjourney shows even greater efficiency, with emissions 2,900 times lower than those of a U.S. artist and 370 times lower than an Indian artist’s emissions.

Andrew Torrance points out that these figures will likely shift as technology and society progress.

The researchers emphasized that carbon emissions are just one aspect of the broader comparison between AI and human outputs. Currently, AI technologies often fall short of matching the quality that humans can achieve in writing and art. However, as these technologies advance, they could both displace existing jobs and generate new ones.

The potential for job loss raises concerns about economic and social instability. Therefore, the authors suggest that the most effective approach might be a collaborative one, where AI and human efforts are combined. This way, AI can enhance human efficiency without fully replacing the human role, allowing individuals to maintain control over the final outcomes of their work.

The authors also highlighted legal concerns, like the use of copyrighted materials in AI’s training data, and noted the possibility that an increase in AI-produced materials could lead to higher energy consumption and emissions. Despite these challenges, they advocate for a partnership between AI and human efforts as the most advantageous way to leverage both.

Andrew Torrance clarified their stance, stating, “We’re not claiming AI is inherently beneficial or superior overall. Our findings simply indicate that in the cases we examined, AI used less energy.”

The study aimed to enhance comprehension of AI’s environmental footprint, aligning with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals focused on sustainable consumption, production, and climate change action.

The authors themselves have started using AI to draft their writing, acknowledging the importance of thorough manual editing and refinement to ensure quality and accuracy in their work.

Andrew Torrance expressed enthusiasm about AI, saying, “This is not a curse; it’s a boon. I believe AI will enhance writing skills, democratize the field, boost productivity, and empower people. I’m very optimistic about technology improving and reducing our environmental footprint. This study is just the beginning, and I hope it sparks more in-depth research into AI’s impact.”